This is a summary of the story and key lessons from the 1984 classic The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement by Eli Goldratt that introduced the world to the Theory of Constraints. Goldratt has published multiple editions of the original book, and also adapted the TOC concept to project management theory with his book Critical Chain, published in 1997.

The Theory of Constraints (TOC) is an operations management method that views any system as being limited in achieving its goals by a small number of constraints. Every system has at least one constraint. TOC uses a focusing process to identify and eliminate the constraint, therefore raising the output of the entire system.

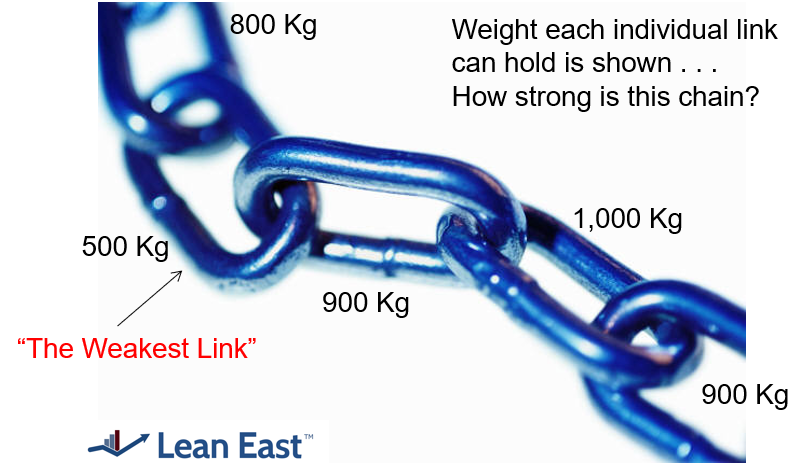

“No Chain is Stronger Than Its Weakest Link”

The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement

The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement by Eli Goldratt has sold over 6 million copies and is one of the top-selling business operations books of all time.

The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement by Eli Goldratt has sold over 6 million copies and is one of the top-selling business operations books of all time.

The book tells the story of plant manager Alex Rogo, who has 90-days to save his plant from being closed by corporate headquarters. Alex and his plant management team evaluate the financial and performance measures. Then they create a turnaround strategy. Alex reconnects with an operational improvement consultant who helps change how he thinks about productivity and inventory. The book also details how Alex deals with a struggling marriage and learns a key lesson from a boy scout during his journey to improvement.

Herbie, the Weakest Link

One of the key lessons about TOC from The Goal occurs during a boy scout camping trip. Plant Manager Alex Rogo volunteers to lead his son’s boy scout troop on a 10-mile hike to a campsite. Soon after beginning, the hikers align themselves with the fastest hiker at the front of the line and the slowest boy in the back. Alex keeps calling for the front of the line to stop and wait for the others to catch up. He soon realizes that the entire rate of the group is limited by the slowest hiker (the constraint) – a boy named Herbie.

First, Alex tries to put Herbie at the front of the line to keep the group connected. This helps, but continues to limit the overall output.

Next, the troop tries to improve the constraint. Upon examining Herbie’s backpack, they find he has packed in over 40 pounds of gear, including canned food and an iron skillet. The rest of the boys each take an item to limit Herbie’s load. Alex quickly sees how the troop is able to get back to it’s expected pace by doing everything they can to improve the constraint (Herbie’s pace).

The Theory of Constraints

The Goal shares a five-step process that is at the heart of the Theory of Constraints.

- Identify the system’s constraint. This is the bottleneck of the system and often identified by piles of inventory just ahead of the constraint or having the longest backorders in that operation.

- Decide how to exploit the system’s constraints. Focus your improvement efforts on redesigning the process to maximize the output from the constraint.

- Subordinate everything else to the above decision. Don’t get distracted or unfocused, and don’t worry about the other steps in the system that are not the constraint (yet).

- Elevate the system’s constraints. Implement the process improvements, reduce idle time, use buffers to keep the process operating, and build additional capacity in your constraint.

- If in the previous steps a constraint has been broken, go back to step 1. Fixing the primary constraint must create a new constraint. Identify the new constraint and now focus your efforts there!

Four Typical Structures:

Alex uses this five-step process to improve his overall plant output and save the plant from closure. In the TOC, it is important to consider your production structure as you are identifying the constraint. There are four typical structures to consider (V-A-T-I structures), each denoted by a letter that represents the structure as you move from the bottom of the letter to the top of the letter:

- V-Process: Material flows from one to many, such as when a single raw material results in multiple finished products. The primary problem is “stealing,” where one operation uses material needed at another operation.

- A-Process: Material flows from many to one, such as a manufacturer where many sub-assemblies are combined into a single finished item. Synchronizing the converging lines is the primary problem.

- T-Process: Material flows from many to many, resulting in both synchronization and stealing issues.

- I-Process: Material flows in sequence, such as in an assembly line. The constraint is the slowest operation in the line.

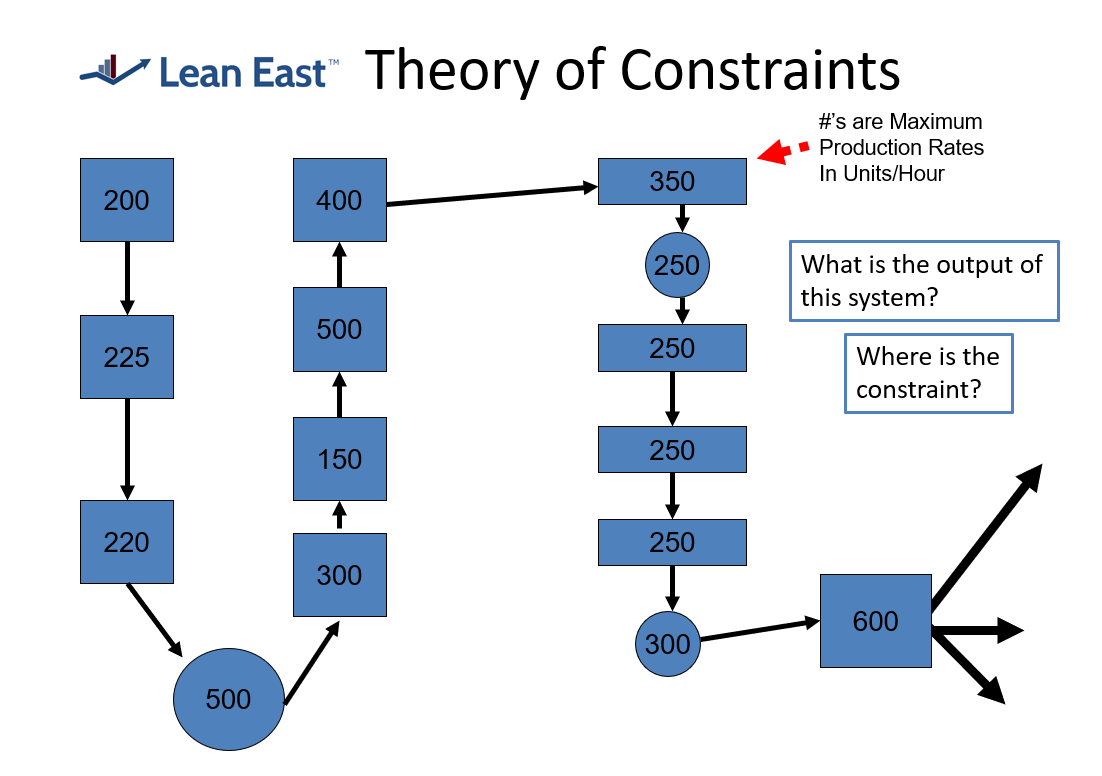

Assembly Line Example

The image below shows the output from an I-Process, or an assembly line, operation. What is the output of this system? Can you identify the system constraint?

In an assembly line process, the constraint will be the operation with the lowest output in the system. This is the bottleneck of the system, and what will limit the output of the entire system.

In an assembly line process, the constraint will be the operation with the lowest output in the system. This is the bottleneck of the system, and what will limit the output of the entire system.

Applying the Theory of Constraints results in several important lessons:

- The output of the entire system will be equal to the output of the constraint.

- Improving any operation that is not the constraint will have no impact on the output. Only improvements to the constraint will make a difference.

- Improvements to the constraint will result in improvements to the system, and eventually, shift the constraint to a new operation.

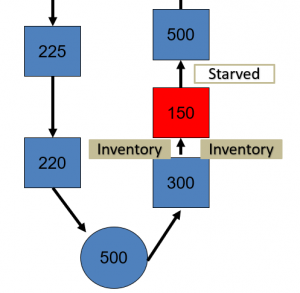

In the example above, the output of the entire system is 150 units per hour. Upstream processes will tend to overproduce and build up inventory in front of this process. Downstream operations will not have any parts to work on and will be starved.

In the example above, the output of the entire system is 150 units per hour. Upstream processes will tend to overproduce and build up inventory in front of this process. Downstream operations will not have any parts to work on and will be starved.

If you apply the five-step TOC process and improve the output of this constraint to 250 units per hour, (by adding capacity, reducing idle time, working with Lean East, etc.) the overall output of the entire system will be increased to a new maximum output represented by the next constraint. In this case, it’s 220 units per hour.

Importantly, focusing your effort on improving a problem in another operation that is not the constraint will not improve the overall output of the system at all.

Lean Six Sigma and TOC

Many of the advanced methods of managing production schedules, inventory, and financial measurement are equivalent to the proven theories and methodologies of Lean and Six Sigma.

For more information, check out the Lean East descriptions of pull methods and flow. TOC seeks to maintain flow in the process and uses pull methods of scheduling to achieve this.

We will also cover process variation (six sigma methodology) in a future post. Our assembly line example above ignored the enormous effect of variation on an actual process.

We hope you benefitted from this basic description of TOC. Please share your experience with applying the Theory of Constraints or leave a comment with your questions below.

Excellent article, it broke down TOC enough to digest. The book was a great read and this article brings back memories of the boy scout hike.

Well written article – it brings back the memories of joy of reading this book in my adulthood.,

In my mother tongue we read as a serial in weekly magazine – I recall how thrilled it was .,

Good work

Excellent and complete… Thanks